Cardiacs – Personal Overview and LSD Review

Personal Overview

I first became aware of Cardiacs early in 1984. The older brother of my own younger brother’s school friend had seen them support Here & Now and liked what he heard. A group of us immediately devoured The Obvious Identity and Toy World cassettes from tape-to-tape run-offs, while The Seaside cassette was one of our most-played albums across 1984 and 1985. I still have every constituent element of the Seaside Treats tote bag. Watch ‘The New General’ from this era (it became the closing part of the original version of ‘R.E.S.’). A group of us went to countless Cardiacs gigs between 1984 and 1988, mostly with the band in their classic six-piece lineup, including Marillion support at Hammersmith Odeon, a stand-out for all the wrong reasons. I followed the band’s studio output religiously through 1992’s Heaven Born And Ever Bright (HB&EB), before veering off in other directions. I renewed my love of Cardiacs in 1999 with Guns (which is perhaps why I adore it so much), following the band to the present and the release of LSD, their valedictory final album.

Cardiacs lyrics combine surrealist collage, absurdist juxtaposition and grammatical dissonance. There are found words – including from nursery rhymes, poetry, phrasebooks and movie dialogue – alongside child-like phrases of marrow-piercing simplicity. There are constant allusions to the horror and the beauty of living, of nature, of being inside a body. In ‘Bodysbad’ (HB&EB) is one of my favourite stanzas from any Cardiacs song; it’s also nicely indicative: “Fiery furnace flew an angel in / Had to take her out and wash her down / Let’s act strong like the old days / A Rizla will fix her wing.” There’s unbearable intensity in that furnace heat. There’s that uniquely English idea of the stiff upper lip, particularly in wartime. The angel’s wing and Rizla paper are a potent juxtaposition; both elements are fragile – one metaphysical, one mundane – but the nature of that mundanity itself suggests experiences beyond the Earthly plane. There’s also a deep vein that speaks to the terror and joy of childhood: playground cruelty and seaside ice cream. There’s the horror of finding a dead animal as a child. The joy of realising that you yourself are not dead. The terror of realising that death waits for you too. The joy of realising that you can actually live before that ineluctable death. There’s the ephemeral adrenaline rush of bullying. The lasting damage of being bullied. The horror of child abuse, which though never directly referenced is always bubbling below the dank surface of Tim’s lyrical domain. There is also grown-up existential anguish, perhaps best encapsulated in the line “left to live out our time on Earth” from ‘Burn Your House Brown’.

There are strong classical resonances in the music, ranging from the modernist to the pastoral, not least the folk-derived works of Vaughan Williams and Arnold Bax. Check out the extended ostinato of Bax’s 1938 orchestrated ‘Paean’ and you can’t help but hear the ostinato sections of ‘In A City Lining’ and ‘The Breakfast Line’. Similarly, listen to the very end of ‘Wireless’ on Sing To God Volume 1 (STGv1) for a faux orchestral climax that sounds like classic-era The Enid, who themselves drew core inspiration from Bax. With Cardiacs, ostinato often drives beyond sonics and modulation into something else. Like the comedy of Stewart Lee, repetition becomes first discomforting then absurd, then again discomforting, then again absurd before arriving at a Zen-like state of awareness of both futility and grace. There is also a stream of musique concrète and found sounds flowing through Cardiacs, which is why they are often compared to Beefheart and Zappa, though in truth the Cardiacs sound has minimal direct relation to American popular-music genres, despite multiple and diverse influences from across the big pond. Unlike Gentle Giant, the Cardiacs sound is almost entirely impervious to funk, soul or blues (notwithstanding blues as source for rock itself) as well as jazz (though there are sometimes occurrences of what Tim called a “snazzy chord”). The musique concrète elements in Cardiacs have more in common with European acts like The Who, Pink Floyd, Brainticket and Throbbing Gristle than with American bands. The Who’s Quadrophenia begins with the sound of the sea. Indeed, the ocean is one of that album’s key thematic elements, another direct connection to Cardiacs. Check out the industrial cacophony in the background towards the end of ‘A Little Man And A House’, a sonic representation of the daily meat-grind in the military-industrial complex worthy of Killing Joke at their most dissonant.

Cardiacs also tap into deep-networked mycelium filaments of English folk but, almost uniquely, combine that folk sensibility with a suburban aesthetic. The only other band to do this to the same extent is XTC, who similarly found a continuity between sacrificial bonfires on chalk hills and both the horrors and absurdities of English suburban life, expressed in Cardiacs through squalor, plastic dolls and incessantly barking dogs. In Cardiacs, this suburban horror and absurdity – often specifically the horror and absurdity of childhood – is often juxtaposed with the horror and absurdity of the First World War.

Tim learnt how to read and score music by osmosing a Quadrophenia song book and there are myriad resonances of The Who across the Cardiacs oeuvre, especially in terms of the brass scoring, which in the early years is far closer to The Who than, say, The Beatles. It’s easily forgotten that Quadrophenia also features violin and piano throughout (and cello), the songbook obviously providing Tim a template for rich instrumental arrangements within a predominantly rock format (listen to ‘Doctor Jimmy’ for a handful of Cardiacs resonances). Tommy also has multiple touchpoints with Cardiacs, sonically and thematically, especially in terms of post-war disassociation and suburban dysfunction. Listen to the original ‘Fiddling About’ for brass deployed at perhaps its most squirm-inducing. Indeed, you could argue that both Quadrophenia and Tommy inspired in Tim a combination of compositional complexity and raw immediacy that is so fundamental to the Cardiacs sound. In Cardiacs, brass suggests not only a traditional English bandstand (listen to the end of ‘The Dirty Jobs’), but also working-class pit bands and military marching bands, the last which again ties specifically into the First World War as a key theme across all Cardiacs lyrics, though especially during the six-piece lineup. In counterpoint, strings suggest country estates and upper-class drawing rooms. They also resonate with the pastoral, as do Dave Gregory’s gorgeous string arrangements for XTC, with which later Cardiacs arrangements have much in common in terms of sonics and affect.

Other than XTC and The Who, there are a plethora of bands that seep through when listening to Cardiacs, Tim being extraordinarily eclectic in both his listening and direct influences. The Kinks are a clear influence (the only cover version recorded by Cardiacs is Dave Davies’s 1967 single ‘Susannah’s Still Alive’), as are prog heavyweights Genesis (in their Gabriel guise where the strangeness and violence of childhood is also key) and Gentle Giant, whose own eclecticism is of a similar order of magnitude to that of Cardiacs. I always hear Van der Graaf Generator in the six-piece lineup: that combination of vocal anguish, saxophone-heavy distortion, epic sustained keyboard chords and a properly heavy bottom-end, the last two of those down to the contributions of William D. Drake. It’s also worth mentioning Here & Now again, a band with whom Cardiacs gigged many times in the early days and for whom Tim was first a guitar tech and later intermittently mixed their live sound. Although there are obvious differences, Here & Now are also at core psychedelic, while having a myriad of other influences including art rock and reggae. This eclecticism – plus the creation of an entirely organic sound out of one’s influences – is something that they and Cardiacs share. They also share the consistent ability to write songs that you can sing along to, that ear-worm into your apple core, that burrow into your mitochondria and nibble at it from the inside.

Although it’s not a fan favourite, HB&EB is probably my most-played Cardiacs album, mainly because it’s chock full of 7”-single-length rock bangers (only the last track runs over five minutes). Like Killing Joke’s Extremities, its mood of sinew-taught anguish and pre-emptive mourning also heralds the neoliberal 90s with extreme prescience. Killing Joke are an interesting comparison, because as well as sharing a handful of musical influences (among them punk, industrial, classic prog and ska), Cardiacs and Killing Joke originally comprised members whose birth years cluster around 1960. This is also true of the first wave of neo-prog bands (excluding Pallas, who originally formed as Rainbow in 1974) and of JG Thirlwell. By contrast, the original members of XTC, Sex Pistols, The Damned and Gang of Four have birth years that cluster around 1955. This five-year differential is important. Both in terms of what is held onto and what is rebelled against. At early adolescence (11-14) it means A Saucerful of Secrets vs. The Dark Side of the Moon. It means In the Court of the Crimson King vs. Larks’ Tongues in Aspic. It means The Who Sell Out vs. Quadrophenia. It means The White Album vs. Red and Blue. (Full disclosure: my own first full-impact contemporary Floyd album was The Wall, me being an archetypal first-wave Xer.) Not only, as Jonathan Pontell argues, is there a meaningful cultural and economic variance between classic Boomers (born 1946-1953) and what he names “Generation Jones” (born 1954-1965), but I would suggest there is also significant differentiation between those who experienced punk as adults (at 19-plus) and those who experienced it as mid-to-late adolescents (at 14-18).

A deeper generational gap is found in the relationship to war, with those born from 1960 onwards being much less likely to have had parents who were adults during the Second World War. This gap is visible in how the multiplicity of narratives surrounding the Second World War from those born between 1940 and 1950 (e.g. Tommy, Arthur, The Final Cut) contrasts with how those with birth years clustered around 1960 deal with war by looking back to the First World War. It’s also the case that by the time of “Generation Jones”, the Second World War was seen almost universally as a moral campaign with a just victory, while the war-crime/jingoism-fest of the Falklands would only be tackled head-on by the bravest of dissenters (e.g. Roger Waters and, apparently via mushroom-fuelled scrying, Killing Joke). By contrast, there are multiple neo-prog works about the so-called “Great War”, including the magnificent (and underappreciated) It Bites concept album ‘Map of the Past’, Twelfth Night’s epic ‘Sequences’, and IQ’s ‘Common Ground’ and ‘The Seventh House’, as well as direct and diffuse themes threaded throughout the entire Cardiacs oeuvre (and again you can hear the influence of The Kinks, specifically Arthur’s ‘Yes Sir, No Sir’, in the lyrics whenever the experiences of cannon fodder in battle is foregrounded).

In terms of American music, influences on Cardiacs range across multiple genres, with strands of the Beach Boys, the aforementioned Beefheart and Zappa, Devo and Sparks. Tim himself expressed a love of Tom Waits, Pixies and Mr Bungle. However, with his arrangements and compositional style, Tim always found a way to render a multiplicity of US influences entirely English. And an innate Englishness also suffuses Cardiacs lyrical thematics: the deep feudalism at the rotting core of how the English do mass slaughter; the fierce beauty of island meteorology, flora and fauna; the absurdity of social and sexual interactions when repression is rife; the simmering terror of having to “keep calm and carry on”. Indeed, England as island nation is there in every reference to ocean and shore, reminding us that the sea will sweep us all away in time, just like stoneage dinosaurs. But there is also English humour, reminiscent of everything from music hall and variety to the Goons and Python. Check out ‘Manhoo’ B-side ‘Spinney’ for a nutshell (or in Cardiacs terms a seashell) example of the serene-angst axis that is so absurd you can’t help but laugh your stupid fucking head off, exactly as you would at a Python sketch.

At the compositional level, Cardiacs songs are defined by their immensely sophisticated and multilayered musical arrangements. Some key elements are irregular time signatures and time-signature shifts, a profusion of chord changes sometimes head-spinning in their sheer number and breathless onslaught, disconcerting expansion and augmentation in phrasing and meter, non-scansion of lyrics (or more accurately anti-scansion: a deliberately disconcerting emphasis on a syllable or word not usually stressed), and visceral extremes of tempi, dynamics and pitch. All of these contribute to a sound that is often jarring, disjointed and alienating, in deliberate contrast to the band’s abiding pop sensibility. Intriguingly, Cardiacs music is rarely dissonant in chordal, harmonic or melodic terms, with harmonic dissonance reserved for bursts of extreme guitar pyrotechnics against a consonant and often ostinato accompaniment.

One of the key left-field elements of Cardiacs compositions is the extensive use of waltz (3/4) and double-waltz (6/8) time signatures, which give especially the early works a sense of wooziness, and for me again evokes the upper classes dancing in country house drawing-rooms as the working class is gassed or blown to pieces in the trenches (“Having a bit of a laugh on the Somme” as ‘Come Back Clammy Lammy’ has it). Or the ship’s band playing on as the Titanic sinks. But again, there is beauty here too: young couples in love, dance-halls, the end of war. A ‘Hope Day’. ‘Vermin Mangle’ – a fragile hymn to both childhood and death, and one of the last song’s Tim worked on before his illness – is also in waltz time.

While Tim’s compositional brilliance is at the core of the Cardiacs sound, his four key post-1983 collaborators all bring something different to the band’s sonic profile. William D. Drake provides epic 70s prog soundscapes, the all-conquering television organ and bottom-end heft (Cardiacs became increasingly treble-forward as time went on). While all three guitarists emerged from bands that were fans of and/or directly influenced by Cardiacs (two bands in Bic’s case: Panixphere and Ring; Jon from Ad Nauseam; Kavus from The Monsoon Bassoon), each of them brings something in addition to a shared penchant for thrash. Bic brings a spiky post-punk sensibility (listen to these mid-80s Panixphere demos; the opening of ‘Intravenous’ became ‘Interruption’ on Ring’s ‘Nervous Recreation’). Jon combines prog precision with feral intensity. Kavus, of course, brings his own psychedelic propensities to the already psychedelia-infused band (he even suggested the title LSD), making the final album by far the band’s most hallucinatory endeavour. Critically, all four also provided Tim with a sonic and compositional foil.

Cardiacs are auditorily and geographically eclectic but English to their core. They are paradoxical in their fiendish complexity and pop sensibility. Their ecstatic joy and abyssal angst. Their placid serenity and seething violence. In short, Cardiacs are a band for nerds, seekers, outliers, dissenters and “gits”.

Vermin Mangle

Although it’s not on LSD, it’s worth considering 2020’s one-off release in honour of Tim’s passing. This not only provides an ideal bridge from the background to my review of LSD, but showcases much of Tim’s compositional approach in microcosm.

When I first heard the title, the word mangle immediately took me to Derek & Clive’s ‘Jump’, the only other place I’d heard the word “mangle” sung. ‘Jump’ is, of course, sung in cod Anglican Chant by Dudley Moore as his foul-mouthed alter ego Derek. As a boy I sang church music, specifically hymns, at primary school, making ‘Jump’ not only transgressive on its own terms but also dissenting in a broader context (cassette tapes of Derek & Clive Live were passed around my boys’ school with the hallowed reverence usually accorded porn magazines). The specific context here is the singing of ‘Morning Has Broken’ at morning assembly, an experience pretty much unique to those born in England between 1955 and 1975, many of us who, irrespective of class, attended church and sang in church choirs even though we were not especially religious, a tradition now almost entirely vanished. ‘Vermin Mangle’ features a musical phrase directly inspired by ‘Morning Has Broken’, though the descending part of that phrase differs slightly across the two pieces (5th/4th/3rd in ‘Vermin Mangle’ vs. 5th/3rd in ‘Morning Has Broken’); the phrases are also in different keys (F# Mix home key vs. C Major home key for the famous Cat Stevens arrangement). The singing of ‘mor-ning’ from root to 2nd at the end of the phrase, however, is the same. ‘Vermin Mangle’ and ‘Morning Has Broken’ are both in waltz time.

Sean Kitching has noted the resonance with Tom Waits in the song’s janky processional feel, and the track definitely conjures a passing parade of circus freaks with Tim as ringmaster (Kitching was immediately reminded of ‘Morning Has Broken’ too). There’s a New Orleans funeral quality to the death-life/grief-joy axis suggested not only by the ‘Vermin Mangle’ time signature but also by the brass that’s so prominent in the arrangement. There’s also what sounds like a banjo (or a guitar mimicking such) which also suggests the American South. But the piano, television organ, swirling end-of-pier keyboards and childlike female backing vocal root this procession as squarely English.

Lyrically, there is pretty much every key Cardiacs element. War is here in “louder than drums” and in the astoundingly raw line “Harder than pulling a soldier off your sister,” where said childlike vocal packs a real punch. Nature is here also, in spring and spawn: evenings, mornings, clouds, leaves, apples, and birds (in particular blackbirds, who are implicit in the ‘Morning Has Broken’ association). There is also nature’s decay and dismay: germs, flies, those titular vermin, “the weeping willows’ dank dark ditch”. There’s that peculiar English nostalgia for (and terror of) family, the post-war dream, that period before Harold Wilson’s “white heat of technology” (1963), notably here the washing machine (Jim’s erstwhile day job) replacing the mangle: “And has your mother sold her mangle / Last time I did saw her, she was in a dream dress.” There’s yearning for the joys and horrors of childhood: “They building a long slide / And along it they glide / Danger all around.” Those lines suggest English 60s/70s PIFs to me. The body is prominent: hands, fingers, eyes. So is the existential anguish not only of living at all, but also of living as an outsider: “Think of a way / Then always go the other way”; “I am the git that walks all by himself.” The vermin mangle is an apt description of life itself, with humans as the vermin that are continuously at war with the rest of nature and with themselves.

The other absolutely core sonic element here is found sounds. Our procession first emerges out of bird song and street sounds. Or maybe we’re hearing a brass band on a bandstand with Tim as the conductor. No, it’s definitely a marching band, but with its oompah strangely deflated. There’s also that Cardiacs-signature dull industrial whining that makes you think of an automated human abattoir. ‘Vermin Mangle’ ends as it begins: with traffic noise. As the main motif fades out, the track drops down to found sounds: a tram bell, vehicle horns, a snatch of conversation, an engine driving away. Every time I hear automobile found sounds in Cardiacs (the car driving away at the very end of ‘The Whole World Window’; the final door/trunk slam at the end of ‘The Duck And Roger The Horse’) I can’t help but think of Floyd’s ‘Welcome to the Machine’, and the Jaguar that drives us to the twat party: a four-wheel machine taking us from one soulless fame-machine to another. ‘Vermin Mangle’ is both sonic and lyric encapsulation of Tim’s magpie approach, but as observed by Jim and Kavus in Kitching’s “The Story of LSD” booklet, the track’s sombre, contemplative mood doesn’t really fit the psychedelic aesthetic of the final album.

LSD Review

The final Cardiacs album runs at a magnificent eighty minutes and opens with an astounding four-track run as strong as anything in the band’s entire catalogue.

Men In Bed

As with HB&EB opener ‘The Alphabet Business Concern (Home of Fadeless Splendour)’, ‘Men in Bed’ kicks off proceedings with a full-bore hymnal assault. There’s that familiar expansion and augmentation, while the brass calls back to ‘A Little Man And A House’. Mike Vennart and Rose-Ellen Kemp share lead vocals to spine-tingling effect while the massed ranks of the ABC provide choral backing. The bed in question suggests ennui, despair and ill-health, but ultimately acceptance of death with a flight of birds as release from life (a bird being a long-standing metaphor for the soul, here represented by Peter and Paul from the nursery rhyme ‘Two Little Dickie Birds’) and a refrain of “I surrender.” But in true Cardiacs fashion this acceptance is contrasted with death’s visceral and violent nature: birds are “blasted free” by those who “would stop the birds from singing”; in death, bodies “they white as pale / They stench all stale as.” It’s the cycle of life as both epiphany and dread. Laudation and bones.

The May / Gen

‘The May’ sits squarely in Sing To God territory, driven by a manic punk-infused 2/4 beat from Bob Leith. Tim’s guide vocal and Vennart’s voice gel perfectly, while the triumphant major 3rd which punctuates the main phrase is typical Tim, as is the downward vocal glissando that ends it. The middle eight and outro guitar soloing from Kavus confirm the same sense of ultra-tight song structure that defines HB&EB. Lyrically, the English pastoral idyll is interrogated through the cursory yet brutal way we treat our so-called livestock, fenced in with the inevitability of our own end: “And the penalty is death for you / If I were your cattle I’d run when I saw you, yeah.” This also calls to mind Killing Joke’s career-long insistence that “man is cattle”. As does this exchange from STGv2‘s ‘Quiet As A Mouse’: “Why would they not be better alive?” “Because we’d have to feed them.” Houses on fire make yet another appearance, resonant with nursery rhyme ‘Ladybird, Ladybird’ (as ‘Men in Bed’ borrows from ‘Two Little Dickie Birds’). The segue into ‘Gen’, my favourite track from the Ditzy Scene EP, is glorious, with Tim’s lead vocal miraculously emerging from ‘The May’. ‘Gen’ itself is a perfectly-formed pop song with an absolutely stonking chorus and a bonkers middle eight which starts with a surf-rock guitar breakdown, comes to a hard stop, and is followed by a classic Cardiacs vocal motif, which slowed down could be The Sea Nymphs.

Woodeneye

Tim hands the lead-vocal baton back to Vennart for the instant classic ‘Woodeneye’. This is a terrific example of even a straightforward rocker playing subtlety with time signatures. There is a sneaky single bar of 2/4 in the chorus that subtly throws-out the temporal alignment of the otherwise (albeit syncopated) 4/4. That major 3rd interval from ‘The May’ comes back, this time exposed at the end of the third verse before a bridge has Vennart and Kemp singing another gorgeous motif an octave apart, this time the resonance being with the On Land And In The Sea (OL&ITS) era. Indeed, some of the imagery is again ship-based: sharks, wooden body parts, treasure and drunkenness. The breakdown features some Auto-Wah silliness from Kavus and a rare bass solo (which hits the 4/4 head-on just in case anyone was wondering about how the song’s time signature is parsed) then it’s back to Kavus for a let-it-rip rock-god guitar solo. Echoing the song’s very first interval, the final chorus refrain (as with the pre-breakdown refrain) then steps up from the song’s root to its flattened sixth before a hard end. Marvellous.

Spelled All Wrong

A big gear shift as ‘Spelled All Wrong’ beds-in the psychedelic nature of the album. It’s a floaty yet mournful mood piece with echoes of XTC, Spratleys and Tim’s sole solo disc, the wonderful Extra Special OceanLandWorld. The main vocal line is a haunting combination of Tim (a guide vocal, which to my ears is the lowest of the three lines), Vennart, and Kemp singing in unison across octaves. This is a good place to mention the deep mind-brain uncanniness of octave equivalence (in essence, although octave-separated notes have different frequencies, the brain hears them as the same due to the mathematical relationship of those frequencies). This is an uncanniness of which Tim makes consistent compositional use. The verses are bridged by some glorious Kavus swooping in Gong-Knifeworld mode. The breakdown is also tripartite: first some sitar-adjacent guitar, then more of that glorious Kavus swooping, and finally a full-bore octave tremolo, which sounds like pure Tim. After the final verse, a single-note guitar ostinato heralds a return of that sitar-adjacent motif with some very Dave Gregory-sounding glissando strings. The refrain “It pierce my bright side wide open” is one of Tim’s most affecting lines. Again, there’s that combination of agony and ecstasy, a recognition of mystical or psychoactive illumination rooted in the physical. Without body as anchor, the mind cannot experience anything. Without something to transcend there can be no transcendence. Psychedelic in the most profound sense.

By Numbers

‘By Numbers’ sounds like something from the first two cassette “demo” albums by way of Sing To God. There’s a magnificently silly bare voice intro, a classic Cardiacs chord progression, a hummable guitar-piano melody, a propulsive ascending-descending bass line, weird chuntering and shouted interjections. Vennart’s vocals (described as a “croon” in “The Story of LSD” booklet) are a perfect fit, plus there’s that major 3rd again at the end of the verses. The ending is pure Cardiacs with a dropdown to guitar, some feedback, a final drum hit and a yell of exasperation. Over the entire oeuvre, non-verbal expressions of disgust, rage and frustration proliferate, as they do across the vocal work of Jaz Coleman with Killing Joke. And good luck working out the multiple time signatures of this one (it took me well over two hours).

The Blue And Buff

This is a short and sweet Kinks-inspired pop number with Vennart and Kemp again in unison. There’s a propulsive drum pattern, a motif straight out of ‘Arnald’, a delicately meandering guitar line, a multilayered closing breakdown with some Kavus guitar-revving and a hard out. It’s yet another reminder that Tim could as easily pen a sub-three-minute pop classic as score a multi-section progressive epic.

Skating

And, as if by magic, here’s one of those multi-section epics, indeed the very last of them. A widescreen love-in gives way to a Guns-era stomp, which resolves into a unison riff. Things immediately get woozy as we start to come up, with echoes of The Beatles at their most lysergic. One of those manic Cardiacs fairground rides (or is it an 8-bit video game soundtrack re-scored?) takes us over the middle. Then, just after the five-minute mark, there’s one of those radio-scanning bits where instead of found sounds, everything is (we assume) studio-recorded. We cycle through swirling organ, spoken words, surf-rock guitar and breathy female vocals. A drum brake heralds an enlightenment-seeking guitar motif then we dissolve into a gorgeous psychedelic swirl with an ethereal Jo Spratley vocal line and a full-blown Kavus trip-out. Finally, there’s an absolutely benchmark Cardiacs outro. It’s the pinnacle of LSD’s trip and what a high it is.

Breed

Stumbling into the chill-out room, ‘Breed’ is a gentle psychedelic pop song with swooning guitar and a mood resonant of ‘Helen And Heaven’ from HB&EB. The Vennart lead vocal is perfectly pitched while the Jane Kaye backing vocal adds gossamer floatiness. The whole album is, of course, suffused with death and endings, but my favourite iterations are right here: “All the mice away and leave” (even the friendlier mice are, like rats, leaving the sinking ship), which is soon followed by instructions to “Lower the coffin now put in the corpse”, summing up the backwards absurdity of death with Milliganesque acuity.

Volob

Continuing in more relaxed vibe, ‘Volob’ is a romance that combines folk-ska verses with a rousing chorus straight out of the OL&ITS era. Kemp’s vocals are as pitch-perfect here as Vennart’s have just been and at this point it’s worth highlighting the astounding job that Jim and Kavus have done wrangling multiple voices (thirteen by my count excluding the final track). Every song feels totally organic, as though the vocals were planned exactly that way from the very start. It’s nothing short of miraculous. At the second verse there’s a brass arrangement that is pure 60s, embedding the sense of flower power (“Flower day!” / “Flower moon!”) in both senses (the hippie dream of love conquering all and ecstatic pollination). Indeed, the lyrics are suffused with nature mysticism, though as ever this beauty is undercut by having to wank when one’s love is elsewhere: “I miss – miss you tug my hair / Last night tug myself / It not the same.” This really is the epitome of Tim’s dichotomous aesthetic. The ecstatically transcendent rubbing right up against the perfunctorily mundane, which is the only way that life can be when you live inside a body. [The title of this piece – “With third eye wild” – is a lyric from ‘Volob’.]

Busty Beez (Instrumental)

Venturing out of the chill-out room we’re whisked away to Helen’s wonderland by fairground train. The ringmaster clips our ticket which turns into a lark, flaps off its beak and flies away. There’s the sound of foghorns. The carriage turns into a big ship, which sails through endless waves as breakfast in bed is served: walking on eggshells, magic beans and burnt toast. The ship’s band wear matching suits. Confetti is everywhere. A faded poster announces Lynda Lydian, who takes the stage. The fat lady is singing but the trip is still in full swing. She’s singing so high that all the glass shatters, the shards becoming a swarm of bees. Clockwork bees. But the clockwork bees are busted, their wings falling off. Immediately everything winds backwards and champagne is served. Dogs consider the quality of atoms while the ship dissolves and now we’re floating in the starry skies with a million points of piercing white light. The whirling dance of a fathomless universe. Up, up and up towards the horizon where everything coalesces into a single point, from which emerges a sofa, quiet as a mouse. Snakes beckon for us to sit. We close our lovely eyes and take a deep breath. Lucy’s not done with us yet.

Lovely Eyes

Another psychedelic pop song, but this one has a darker hue as dread starts to drip into the trip. Vennart and Kemp are again in octave unison with Vennart foregrounded. We start with a rolling pop motif with strings, but this is immediately undercut by the insistent second motif, which is ‘Ideal’-adjacent and recalls that song’s manic stop-starts. There are images of hippie-trail transcendence: “crazy colours”, “the distant East”, but as ever horror and beauty are hand-in-hand. “Magic is final”, as anyone who has opened their own psychoactive doors knows full well: this is an irreversible journey for good and ill, you cannot unknow once you have known, “prohibited and all very strange”. The breakdown starts with the initial motif punctuated by guitar chops as some prime Kavus riffage fades up. An A Little Man And A House And The Whole World Window style string interlude is followed by a Sing To God style rock out. Then the two sonic strands merge: the serene and the febrile intertwined. The final verse’s final image is “Blood is the clothes you wear.” Like a peacenik at Kent State. The hippie dream already flayed to bones. It’s the whole album in microcosm.

Ditzy Scene

After the trip has threatened to go very bad indeed, things again calm down, but we’re soon thrust back into something like a cross between a tie-dye-thronged happening and a surrealist nightmare. We start with the same woozy guitar chords and pensive guitar line as the original EP version, but in this beautifully polished iteration the guitars are soon joined by added brass, in a Beatles-style arrangement. While the music appears celebratory – another in a long line of anthemic hymns – the lyrics are anything but. There are “hungry mouths”, a “baying million / All charred, all hearts full of hurting,” and a plea to “cease this lynching army”. The final couplet is as dark as it gets, the scene turned from joyously frivolous to apocalyptic. And there’s one of my favourite lines by anyone (Kavus in this case): “Luck’s ferocious left hand stalled.”

Downup

To a funky drummer adjacent beat, a Vennart sole vocal invokes the frenetic energy of the Sing To God and Guns era with this archetypal Cardiacs track. We start with the chorus, which transmits the Sisyphean futility of most of our live-out time on Earth. By contrast the verses commence optimistic, suffused with the ephemerality and fragility of love, “lived careless but honestly”. Again, there is reference to the widdershins inclined, “This careful love cack-handed,” as we’re invited to “grow an ideal”. Verse two takes a darker turn with “a dungeon full all of his own” and verse three takes us back to childhood and a suggestion that love’s delicate bug is having its wings ripped off. A riff-roaring Kavus guitar solo provides some respite, but the chorus refrain and outro leave us with the unshakeable idea that love is storm-tossed at best while life itself must be choked down and sucked up “with a grin”.

A Roll From A Dirty Place

Our juices now being up, it’s time for some dirty fingering. On frets or otherwise. This is another Vennart-Kemp vocal, this time a fervid erotic nightmare that sounds like we’ve found wonderland’s cinema room, in which both Eraserhead and Last Tango in Paris are unspooling onto opposing fluids-stained sheets. Yes, the opening phrase (specifically the first five notes) is reminiscent of ‘Happy Jack’, but that’s it. The rest of this song’s verse motif cycles through two key changes (E Mix to A# Lydian to D Minor, the latter two keys having the same notes) before it arrives back at E Mix (The Who song verses stay resolutely in D Major throughout). Ironic that in ‘Happy Jack’ “The kids would all sing,” but it is Tim who so often takes “the wrong key”. Also worth mentioning that although ‘Happy Jack’ has none of the time-signature craziness of this track, it does interpolate a single sneaky bar of 2/8 into verses that are otherwise in 4/8, which is similar to what ‘Woodeneye’ does in its chorus. After the first two verses (each followed by a benchmark mini-bridge) the main melody is played by the brass, which is again Beatles-sounding (or rather more The Dukes of Stratosphear). That bridge returns, more emphatic this time, to take us into a chorus that starts in waltz time (four bars) then almost immediately goes off and things. There are multiple different time signatures across two sections divided by a 2/4 motif, including by my count a fiendishly syncopated section played over the following individual bars: 4/4, 4/4, 3/4, 5/4, 5/4, 3/4, 3/4. In perfect symmetry, the chorus ends with four bars of 3/4. And this is why we praise him. The chorus includes the lines “I’ve no idea where I am / Tell yourself it’s just a film”: perfect narrative tenterhooks. Oh, and “Carpet my slang!” has now entered my lexicon as an exclamation of amazed disgust.

Made All Up

Unlike the EP version, which commences with what I call the musical box opening, the album version crashes straight into that hypnotic chorus melody, which contrasts perfectly with the waltz-time ending of the previous track. Again, we have a unison vocal across two octaves, this time Tim and Suzy Kirby and here is a fabulously concentrated version of Tim’s use of expansion and augmentation in the phrasing: it’ll take you several passes before you nail this if you’re trying to learn it. And those multi-tracked female cries of “Woooo!” are pure Anadin-sisters psychedelia (or Da Blooz/Wombat for the proper heads). Lyrically we’re “in the dry ground”, buried but maybe still alive. Or half-dead. That state that we are all in from cradle to grave, whether we’re aware of it with the focus of a soldier, or wilfully oblivious till we keel over. Life is a trip. “It’s all one thing, no you can’t wake up out of it or wake up into it.” Following two verses of the guitar playing the main melody, instead of fading out as the EP version does, the album version drops down to organ chords for a verse and ends on a simple piano chord-to-root, which perfectly set us up for the extended come-down of the final track.

Pet Fezant

The last track is both come-down and uplifting hymn to life. Over the years we’ve been shot, gassed, burnt, buried and stomped into the mud by Cardiacs songs. On LSD alone we’ve been through the darkest caves of chapel perilous but now finally emerge on the other side, blinking into the light. The message of this particular gallinaceous bird is uncompromisingly optimistic (while the idea of a fez-wearing ant is joyfully absurd). There’s a Wildean heart to the sentiment but expressed as only Cardiacs can (the lyrics by Emily Jones are flawlessly idiomatic and entirely organic): “That secret colour that is just right / Oh, glory on the ground / As bright as our eyes shine / Glory lies on the ground / All pointing our beaks up into the sky.” Although our bodies cannot fly, our minds can soar. The arrangement is sublime, starting with acoustic guitar but soon incorporating flowing bass, a plaintive guitar line, strings, brass and the massed choirs of the ABC. It’s especially poignant that one member of those choirs is Mick Pugh, who sings on Cardiac Arrest’s 1979 single ‘A Bus for a Bus on the Bus’, thus giving the proceedings an alchemical circularity. A snake, finally free of its ball and chain, now sleeping with its own tail in its mouth. Like ‘Wireless’, ‘Pet Fezant’ lands with some hypnotically transcendent ostinato. As we float back down to Earth, the 4th intervals combined with that ostinato are deeply reminiscent of the live-only set-closing ‘Hymn’, which is in truth closer to Anglican Chant than a hymn in the church sense. As with OL&ITS, but here almost imperceptibly as with STGv2 (HB&EB begins with it), this song, the album, and the entire oeuvre, ends with the Cardiacs ident (which always reminds me of the xylophone opening of Camberwick Green).

But what the fuck is the cover’s kangaroo all about? Well, for a start, kangaroos are deeply uncanny animals, brilliantly described by somebody as “deer who’ve been to the gym”. This particular specimen is obviously a tripped-out boomer (pun very much intended). The down-under animal is also resonant with song title ‘Downup’, which is itself allusive of high-flying skies and deep-diving ocean.

LSD is swirling fractals of paisley surrounding islands of grief, yearning and dread. It is inlets where sensuous ripples reflect the sun. It is hidden coves in which sixty-year-old sand castles still stand. It is jagged rocks on which life dashes you till you’re bruised and bleeding. And it is that one high cliff, from where you fall into the forever depths of the ocean, surrender to The All and join the plankton.

Most of all, LSD is a joyous memorial to Tim’s genius and a testament to the love, support, loyalty and craft of those who worked variously with Tim across almost forty-five years, especially his brother Jim.

“We are those whose thunder shakes the skies

Whose eyes this atom globe surveys

Thy justice fear

Hooray!”

In 1985 I interviewed Tim for my fanzine The Stairway. I have scanned and uploaded that interview here. This piece is the first time I have written about Cardiacs since then, a span of 40 years.

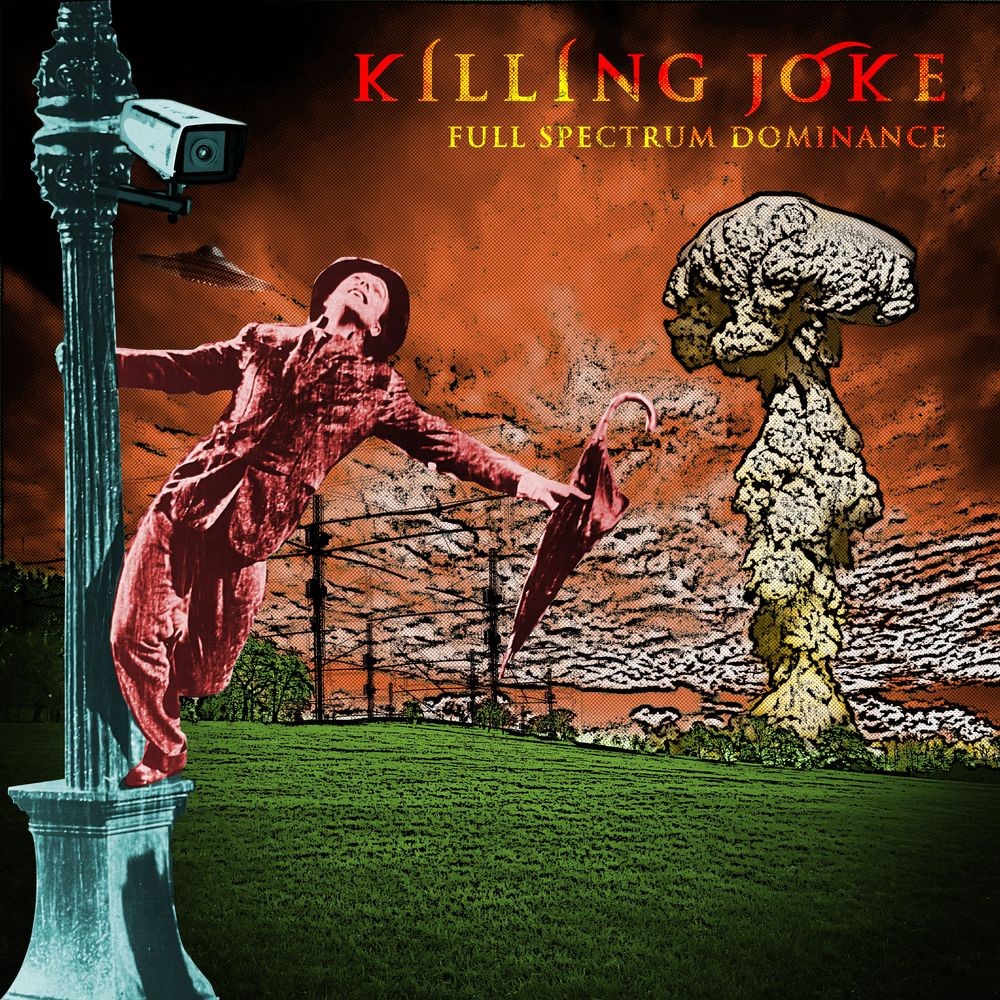

My book about Killing Joke is here.