Part Two

(Part One on Life Of Brian is here, including an introduction to the series)

[As is, again, the way of things, this part has now been delayed by almost two years. My original intention was to post each of the four parts on the 40th anniversary of the original UK cinema release of each of the four films, but other things continue to get in the way. Or maybe I should spend less time on Twitter. Expect Part Three by June. That’s June 2023, most likely.]

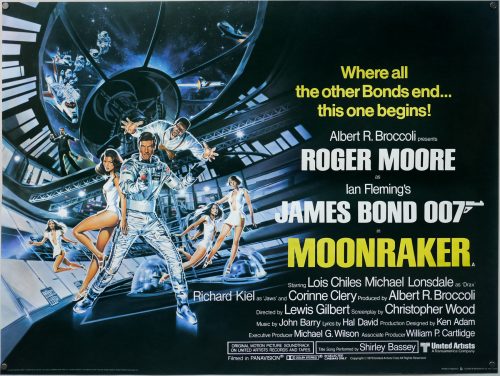

MOONRAKER

ORIGINAL UK CINEMA RELEASE WEDNESDAY, 27TH JUNE 1979.

‘A’ certificate. Not suitable for children under 8 years of age. No dodgyness required!

With ginger Drax and scary Drax recently heading to the edge of space/space—and baby-face Drax not too far behind in person, but way ahead in terms of aspiration—it feels like an apt time finally to post Part Two of this short series about the four films released in 1979 (my twelfth year on planet world) which had the most profound effect on my psychological development. Orbiting Moonraker’s ultra high-concept plot, breathless action and broad comedy are themes and ideas that helped to shape my world view and political identity. Themes and ideas that have stayed with me over the next 42 years.

Moonraker (on balance not only my favourite Bond—just edging The Living Daylights into second place—but one of my favourite films at all) premiered in the UK on 26th June 1979 and was released on 27th June, which also happened to be my twelfth birthday, making it particularly special, especially as I’d been a Bond fanatic since seeing Diamonds Are Forever as a four-year-old (see Part One). As with all of these four films, I saw it at the Sevenoaks Odeon on the first day of release at that cinema, so either on the 27th (which is what I recall) or Friday 29th if the film didn’t go wide till then.

Moonraker also has for me the additional frisson of subsequent location-recognition, due to a family holiday to Venice in the spring of 1980 (more on this in Part Four) during which we visited the glass-blowing workshops (like this one) on Murano and Burano, the trip being something of an inadvertent pilgrimage for me (and the first of many visits to film and TV locations over the following decades).

Add to all of that one of the most underrated title songs of the franchise, a sublime Barry score (it’s no coincidence that superior franchise entries brought out Barry’s very best) and the most gloriously idiosyncratic villain bar none, and you have a film beloved by true connoisseurs, but still mocked, overlooked and misunderstood by both Bond fans and movie geeks.

FOUR KEY THEMES:

1. Psychopath billionaires.

“First there was a dream.

Now there is reality.

Here, in the untainted cradle of the heavens,

will be created a new super-race,

a race of perfect physical specimens.

You have been selected as its progenitors, like gods.

Your offspring will return to Earth and shape it in their image.

You have all served in humble capacities in my terrestrial empire.

Your seed, like yourselves, will pay deference to the ultimate dynasty

which I alone have created.

From their first day on Earth they will be able to look up

and know that there is law and order in the heavens.”

Like Musk, Bezos and Branson, Drax is “obsessed with the conquest of space.” Indeed, he has terraformed his own personal Versailles in the Californian desert, both a stark foregrounding of Drax’s psychopathy and a clever misdirect of Drax’s true masterplan. A piano-playing aesthete with a nice line in drollery: “May I press you to a cucumber sandwich?”; “See that some harm comes to him,” Drax, as exquisitely played by the late Michael Lonsdale, is the most prescient precursor of the world in which we now live—and the inescapable gravity of its power structures. As the doomed Corrine tells Bond on the helicopter flight to Drax’s estate, “What he doesn’t own he doesn’t want.” One has to imagine that a small but not insignificant number of people watched Moonraker on first release and thought: Why would I want to be Bond? He has bosses. I want to be Hugo Drax. No-one tells him what to do.

It wasn’t until I was about fifteen that I realised that both the ladies of Europe’s minor aristocracy (presumably the aristocracy proper would have wanted to be in charge) and the new money heiresses to whom Bond is introduced by Drax—pair one, Countess Lubinski and Lady Victoria Devon at afternoon tea in the palace; pair two, Mademoiselle Deladier and La Signorina del Mateo at the pheasant shoot—are not only aligned with Drax’s idea of “perfect physical specimens” but are also perhaps helping to finance his project. At the very least they have been selected for Drax’s masterplan not just for their beauty but for their status. This is so close to the rich and famous buying seats on civilian spacecraft forty years later that the accuracy of Moonraker’s predictions is truly astounding.

It isn’t only millionaires and the landed gentry who are in Drax’s pocket. When Bond humiliates the Minister by taking him and M to the miraculously-vanished Venice laboratory, the Minister’s outrage is expressed in the fact that he has “played bridge” with Drax. The Minister goes so far as to apologise to Drax “on behalf of the British Government.” This is again hugely prescient and politically astute. A nation state in thrall to an oligarch. The US-UK military-industrial complex exploited for personal gain by a state-agnostic billionaire. And that oligarch clearly with power over both governments, while Britain, trapped between forces far stronger than itself, suffers delusions of grandeur. Thank Fleming for soft power!

Unlike Stromberg and multiple other franchise villains, Drax has no interest in playing the US off against the Russians. His ambitions are geoplanetary rather than geopolitical. The issue of tax is never raised—I mean, this isn’t Ken Loach—but you can guarantee that Drax hasn’t paid a cent for a very long time indeed.

Bond causing the British government such embarrassment means he is taken off the assignment and must go semi-rogue on his “two weeks leave of absence,” with M’s unofficial blessing but without official government sanction, arguably the first time Bond goes rogue in the franchise after On Her Majesty’s Secret Service (OHMSS), and the only time that Moore’s Bond does this at all (although he is removed from the case in The Man With The Golden Gun (TMWTGG), he proceeds to pull at a different thread).

The earthbound geopolitics of it all—some nation states far more powerful than others, but billionaires more powerful than any nation state—is again underscored in the Brazilian monastery where the bolus assassin explodes the head of a mannequin obviously representative of a South American “dictator”. Britain, always happy to help with regime change. The one moment where there’s cause for optimism is when the American and Russian top brass liaise over a possible existential threat to everyone on planet Earth. Maybe that really is the only thing that will make us stop fighting each other.

You could try to argue that Drax isn’t the best Bond villain, but you’d be wrong. Drax works so well because he is both a forecast of our post-capitalist billionaires and an articulate prophet of ecocide, climate breakdown, over-population and shrinking resources. He’s also smart (vanishing his Venice laboratory overnight), wonderfully dry of wit, and almost entirely unflappable. His villainy transcends both money (SPECTRE) and geopolitics (SMERSH) and has a motivation to which we can all, at some level, relate. Indeed, is there another Bond villain as relatable as Drax? Is there a better baddie zinger—or more effortlessly delivered—than: “James Bond. You appear with the tedious inevitability of an unloved season.” And he provokes one of Bond’s franchise-best zingers in return: “Take a giant step for mankind.”

Verdict: psychopath billionaires—bad.

2. Ecocatastrophe.

One can make a strong case that Drax is the archetypal wrong-headed antagonist, trying to do the wrong thing, in the wrong way, but for the right reasons. Even better, notwithstanding some obvious collateral damage, his motivations and actions are always perfectly aligned, unlike The Spy Who Loved Me’s Stromberg, who claims to love aquatic life but is quite happy to annihilate millions of innocent sea creatures with nuclear strikes and the subsequent fallout, not to mention that his entire plan to rebuild civilisation underwater is deeply flawed.

Moonraker is clearly a re-tread of The Spy Who Loved Me (TSWLM) in many ways (and the two films make a perfect double-bill, with Jaws as the secondary antagonist both times), but Christopher Wood and Lewis Gilbert have endeavored to close all the plot-holes so evident in their first attempt. Though having said all that, Drax’s love of nature clearly does not extend either to pheasants or to the inhabitants of rainforest rivers, a subtle indicator of his obvious hypocrisy.

The Black Orchid or “Orchideae Negre,” is the most crunchy and layered of all devices used by Bond villains across the franchise, far more interesting and allusive than yet another nuclear device. It’s so wonderfully apt that the destruction of humankind, which has so befouled its own ecosystem and treated its cohabitant species with such utter contempt should come from a flower.

Drax tells Bond that “one must preserve the balance of nature,” something that the fictional civilisation who lived in the city on whose ruins Drax has built his rainforest base failed to do, dying out due to sterility caused by the orchid’s pollen (though Drax has, of course, “improved upon sterility.”). Here again is the Atlantean theme of hubris: like all civilisations the current one will end, even though we believe we are both invincible and indestructible.

Verdict: ecocatastrophe—bad for humans, great for everyone else.

3. Eugenics.

Drax’s plan to repopulate the world with the cast of Love Island: Aristocracy Special is, of course, all rather Nazi, especially in terms of Drax’s decidedly un-Aryan appearance (isn’t it bizarre how proponents of eugenics almost never look like their ideal human?), notwithstanding that Drax’s astronauts are indisputably multi-ethnic, a clever wrinkle that means while he can be accused of eugenics, Drax cannot be accused of racism: unless it’s against the entire human race that is.

There is also clever resonance with the mythically-superior Amazon women when Bond lands his hang glider and follows a white-robed astronaut to an entirely fictional Mesoamerican temple (even though there were neither Mesoamerican or Inca civilisations in what is now Brazil; the temple used is actually Guatemala’s Maya Tik’al Temple). There’s even a von Däniken-esque hint that the gods who seeded ancient human civilisations are now returning to space in order to start the process again (presumably they aren’t happy with the current iteration). Drax’s monologue quoted above has particular thematic complexity when read through this strand.

The quasi-Aryan plot strand also foregrounds another piece of clever self-reflexive business. Bond films have a tradition of blonde-haired, blue-eyed baddies/henchmen going as far back as Robert Shaw in From Russia With Love (the Übermensch and homoerotic elements are stark in the scene where Rosa Klebb examines the near-naked Red) and used again to knowing effect in The Living Daylights with Necros (it’s no coincidence that both films were written by Richard Maibaum).

Moonraker takes this trope and magnifies it so that the entirety of the threat to the human race is a quasi-Aryan take-over (led, of course, by an aging villain with brown eyes and brown hair). The way that Bond convinces Jaws to defect to his side due to the obvious lie that Jaws and Dolly—and their offspring—could ever be considered part of Drax’s “master race” is a critical plot beat, without which Bond would fail in his mission.

Verdict: eugenics—definitely bad.

4. Diversity.

Tying directly into the eugenics strand but in direct opposition to it—and clearly the film’s key message: the compassion of the honourable and the humble vanquishes the bigotry of the rich & powerful—another example of Moonraker’s prescience is its trail-blazing and oft-ignored diversity. Especially seen in light of its budget and the consequent risk if the film had failed (its budget was more than double that of TSWLM in actual dollars; Moonraker was the most expensive Bond film in adjusted dollars till Tomorrow Never Dies).

Dr. Goodhead is a bona fide rocket scientist (the name both a gimme to double entendre tradition and a punning observation of Goodhead’s brainiac credentials). It is Goodhead who pilot’s Moonraker 6 into orbit while Bond is literally a passenger. “Hashtag feminism” as John Oliver would say. When Bond first meets Goodhead, he is stunned she’s not a man, neatly puncturing the default misogyny of the late 70s. She’s sharp, dry and witty—a perfect foil for Moore’s effortlessly debonair male entitlement. Bond and Goodhead’s relationship is a guarded one throughout. Even when they sleep together in Venice they each have an agenda. Thereafter their relationship is kept mostly professional till its unguarded consummation in the denouement—which they’ve both surely earned.

The key twist is, of course, Bond’s appeal to Jaws and Dolly, an exquisitely well-written and beautifully played scene. Jaws is smart and Bond respects Jaws enough to acknowledge this. Jaws immediately understands the import of Bond and Drax’s exchange, in which, cunningly provoked by Bond, who plays to Drax’s egomania, Drax confirms that anyone not measuring up to his “standards of physical perfection” will be “exterminated”.

I challenge anyone to watch the moment that follows, in which, after Jaws and Dolly have fully understood Bond’s observation, Drax attempts to command Jaws (“You obey me! Expel them!”) and not be moved by the dramatic and thematic rigour of this exchange. And by the respectively high-impact and wonderfully under-played performances of Lonsdale and Kiel.

Dolly is also very deliberately differentiated from the traditional “Bond girl”. But Dolly is also deaf, and in an artfully paid-off plot turn, her lip reading enables Jaws to free the jammed docking-release system that allows Bond and Goodhead to track the lethal orchid globes in Moonraker 5 and save the day. The fact of their physical difference is never at the expense of either Jaws or Dolly. Indeed, both as individuals and as a couple, they are the emotional centre of the story. The film is, yet again, ahead of its time.

Verdict: diversity—good.

FOUR FAVOURITE MOMENTS/ELEMENTS:

1. Cone and fin.

Moonraker’s opening is one of the best of any Bond film and perhaps one of the best of any action thriller. Taking its cue from TSWLM, by having the opening sequence be the initiation of the current plot rather than the closure of a previous unseen story, Moonraker ups the ante from, as we later learn, Stromberg’s mega-submarine eating smaller British and Russian nuclear submarines (inspired by the real-life Project Azorian recovery operation) to Drax stealing a Space Shuttle—on loan from the US government to the British—right from off the plane transporting it. Plus it features one of the all-time great diegetic film titles. But then we still get a traditional “previous mission” prologue as well, with a pertinent reminder that Jaws is not to be trifled with. Bonus!

The ending, even though clearly inspired by both the climax of Star Wars and early arcade games such as Space Invaders, is still by far the most nail-biting climax of any Bond movie up to that point. And it’s as far from yet another timer countdown as you could possibly get. Also, it’s hugely superior to the static, anti-climactic ending of TSWLM, which is entirely passive, with Bond watching dots on a screen far away from the actual action (notwithstanding he wouldn’t want to be there, though Indy IV proves there is a way to do nuclear safety ‘on site’ as it were).

And as throughout the entire film, this final set piece features Bond and Goodhead as genuine equals, her piloting Moonraker 5 and him firing, then manually aiming and firing the laser. And neither of them is saving the other; instead, together they are saving 100s of millions on Earth down below. As throughout the film, Barry’s score provides seamlessly dovetailed accompaniment. We end with Q’s ultra-dry fnarr and a snappy exchange between Bond and Goodhead, in which it is Goodhead who has the film’s last double entendre. “Hashtag feminism,” indeed. Perfection.

2. Emotional engagement.

Much of this is due to Gilbert, arguably the classic-era Bond director with the most natural talent for drawing the best out of actors (indeed you could argue that Gilbert directing and John Glen editing is the perfect combination). You rarely see Moore’s Bond as vulnerable as he is immediately after experiencing 13G (a scene which also cleverly demonstrates Bond’s obvious fitness for space, even though he’s had no astronaut training).

In giving Jaws his own arc, and making the arc critical to the main plot, Moonraker cleverly shifts the emotional heavy lifting from Bond to other characters, freeing-up Moore to give one of his very best—and most sardonically effortless—performances in the role. That’s not to say Moore can’t do the emotional stuff. In For Your Eyes Only (FYEO), which was originally due to follow TSWLM but was put back so Moonraker could go first, Moore yet again surprises with his most emotionally affecting performance, assisted by the decision to treat the film as a mid-run reboot (what would probably now be called a “grounded reset,” after the space laser battles and broad tonal palette of Moonraker; and of course its huge budget, though FYEO was still the second most expensive Bond film after Moonraker).

It’s also no coincidence that FYEO has so much in common with The Living Daylights, the next time the franchise was rebooted, this time with a new Bond in Timothy Dalton (both films also share the same writers in Richard Maibaum and Michael G. Wilson, and the same director in Glen). Next time you watch FYEO, enjoy how the rebooted franchise uses its opening sequence literally to dump its previous baggage down a chimney stack in the shape of a Blofeld-style villain (Eon didn’t have the rights to use Blofeld at the time, of course), clearly setting-out its stall that this is going to be a new type of Bond film: more Earth-bound in every sense.

3. Genre.

Moonraker is genuinely exceptional in genre terms. A sci-fi spy action comedy thriller with horror elements and a romantic drama subplot (Dolly/Jaws), it is extraordinary how everything feels organic, from the horror trope of Drax releasing his hounds to chase-down and kill the unfortunate Corrine in the woods after the pheasant shoot (her employment being “terminated”), to the comedy of the coffin-dwelling knife-thrower, the double-take pigeon in St. Mark’s Square and the way Drax calls “dial-a-henchman” after Bond dispatches Chang (part of a supremely elegant midpoint transition sequence).

From the climactic (and genuinely violent) space-laser battle (the absence of the Connery-era standard machine-gun battle ironically adding real weight to each death in the vacuum of space) to the dance of trust and deceit between the two lead spies. The film sets out its wide but never broken genre parameters at the very outset with Bond’s thrilling escape from death by free-fall counterpointed with a parachute-less Jaws landing on a circus big top.

Add to this Drax as a conscious take on a sci-fi/horror mad professor antagonist—doing the wrong thing for comprehensible reasons—and you have one of the most sophisticated genre blends in the history of popular cinema and a genuine trailblazer. Indeed, without Moore’s Bond—and specifically without Moonraker, the most overtly and deliberately comedic of all Moore’s appearances in the role—we probably wouldn’t have the slew of ultra-sophisticated genre-splicing spy-action-comedy movies of the past few years. It might not be too far a stretch to claim that Moonraker pretty much single-handedly invented the postmodern genre mash-up.

4. Screenwriting masterclass.

The Venice night-time break-in sequence is an object lesson in showing not telling. Bond lock-picks his way into Drax’s building, overhears one of the scientists access the secret laboratory with the five-note motif from Close Encounters used as a keypad entry code, and follows suit, a playful acknowledgment of the franchise jumping on the sci-fi bandwagon (even cuter are the opening notes of Richard Strauss’s “Also sprach Zarathustra” aka 2001 played on a hunting horn at the pheasant shoot).

Inside the lab, Bond leaves a vial of clear liquid precariously balanced when he flees to safety on the return of a couple of Drax’s scientists. The complicit boffins disturb the vial, which falls to the floor and smashes, releasing a cloud of gas. The scientists die, clutching at their throats. But the lab rats in a cage are fine. This is Drax’s entire plan in three beats, but subtle enough not to spoil the reveal for most of the audience: rather it’s a piece of perfectly played subliminal foreshadowing, essential for a plot with such a high concept. Of course, there will be a handful of audience members who will work it out immediately (as an insufferably precocious 12-year-old I did just that) but this is advantageous: it binds them both to the story and the brand (as this post conclusively proves).

In terms of set-ups and pay-offs, I’ve always loved the subtle callback to Jaws falling onto the big top in the pre-credits sequence when he follows Bond and Manuela in a Rio carnival clown costume. It’s perfectly in-keeping with the film’s genre multiplicity that the circus/clown trope appears the first time as broad comedy and the second time as genuine horror (a dark alleyway, a solitary female instinctively covering her exposed neck, a horrific monster trying to bite her). But this little cluster of tropes is even more sophisticated, because the vampire bite also pays-off the coffin-dwelling knife assassin. Magnificent.

Finally, the brilliant head-melting set-up of the space laser in the monastery courtyard in which Q is testing weapons, expertly preparing us for the space battle to come.

CODA:

It’s no accident that this year’s Black Widow pays homage to Moonraker in an early scene. Natasha Romanoff is hiding out in a remote static caravan in Norway and is not only watching, but quoting along to Moonraker (it’s the scene at Drax’s rainforest temple launch base, in which Bond fights Drax’s pet python). That’s the first and only thing I have in common with Black Widow—the ability to quote the entirety of Moonraker.

There is clearly deep logic to this, with Eric Pearson and Cate Shortland’s film having both the lightness of touch and deep emotional heft of Wood and Gilbert’s masterpiece (both elements sorely missing from other entries in the MCU), in addition to a Bond-style plot, a Bond-flavoured villain, a Bond-flavoured lair (Dreykov’s sky base has clear associations with Drax’s space station) and a protagonist who—while she’s on screen—renders the idea of a female Bond entirely redundant.

Next up, the third of the Four Films That Made Me: The China Syndrome (1979), in which the human-created apocalyptic threat is entirely earthbound, indeed right through to its molten core…