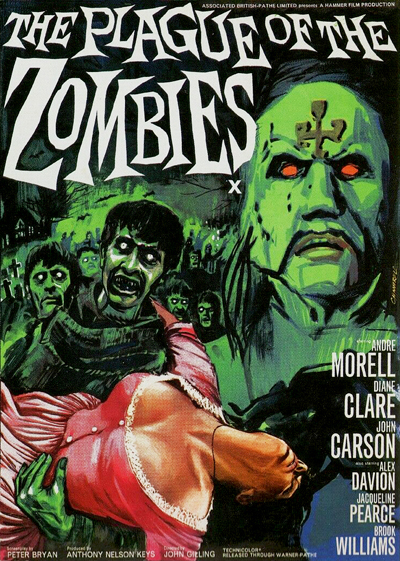

Deep into Hammer’s mid-Victorian set The Plague of The Zombies, villainous Squire Hamilton and the other exclusively male members of his local hunt tease and physically abuse the indefatigably inquisitive Sylvia (though the virulent misogyny on display screams a far darker subtext).

Whenever I see that infamous photograph of Johnson, Cameron and the rest of the 1987 vintage in their Bullingdon Club attire, I’m reminded of this genuinely disturbing scene (you know the photo; for a refresher simply search online as despite permission for its use being withdrawn by the copyright owners, there are plenty of sites still sharing it).

In addition to assaulting young women, the Squire and his landed-gentry acolytes in Plague are exploiting the locals through Voodoo and black magic. They’re killing the village’s inhabitants (the titular plague), resurrecting then forcing them to work in their tin mines as the living dead. Indeed, the death rate is so unnaturally high for the tiny Cornish village, that the local doctor has called his mentor down from London to help (and his mentor’s independently-minded daughter has insisted she tag along).

I’m in something of a unique position regarding what I’m convinced is Hammer’s unassailable masterpiece. Having overseen the restoration of 13 of the studio’s classic films between 2011 and 2013, I’ve probably watched Plague more than anyone except those who worked on the original in post-production. (Other than restoration and grading to restore the film to its original glory, most notably we re-ordered the film’s opening sequence as intended, and reverted to the original 1.66:1 aspect ratio, revealing more of every frame. Detailed review of the Blu-ray release here.)

From this perspective, I can justifiably argue that Plague is the most thematically rich of all Hammer’s horror films, combining an overtly Marxist strand (exploited workers) with stark commentary on English feudalism (the landed class abusing the peasants) along with a generous helping of Freud’s “Return of The Repressed”.

Freud’s concept—the idea that what is repressed psychologically will always ultimately return to wreak havoc—is one of the mainstays of horror cinema and had a profound effect on the generation of North American horror auteurs who arrived then thrived during the 60s and 70s, including most notably George A. Romero, David Cronenberg, Wes Craven and John Carpenter.

Plague was released in both the UK and the US in January 1966, almost three years before Romero’s Night of The Living Dead (NOTLD), the first of the horror master’s Dead sequence. Although the main influence on NOTLD is often claimed as Victor Halperin’s 1932 White Zombie, it’s almost impossible to conceive that Romero was not influenced by Plague also. It is, of course, unarguable that Halperin’s film is the key influence on Plague itself.

In each of Romero’s films, a key element of America’s “repressed” returns as the living dead: in NOTLD it’s slavery and white supremacy, in Dawn of… it’s consumerism, in Day of… it’s US imperialism and Vietnam, in Land of… it’s end-stage capitalism, in Diary… and Survival… it’s the primal instincts repressed by varnish-thin layers of society and technology. In Plague, the repressed that returns is empire, but the location to which it returns (Cornwall) as well as from where it returns (Haiti) are prescient. The Squire and his hench-toffs use Voodoo magic—the fruits of slavery and colonialism—to enslave Cornish villagers.

In fixing the origin of the Voodoo magic as non-British Empire territory, but the location of the exploitation as Cornwall, the film clearly shows the imposition of an empire mindset on England itself: specifically on a part of England that has always claimed its independence from the centre; a part of England which is as much “occupied” by English feudalism as was any part of the British Empire overseas. (For Hammer’s take on the repressed returning from the British Empire itself, specifically British Malaya, watch The Reptile, which was shot back-to-back with Plague by the same director, John Gilling.)

I have long argued that the occupied home nations of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland have since Brexit been run as a de facto inland Empire, with all that this entails in terms of how the people are abused, exploited and discarded by the ruling class. From the loss of Freedom of Movement to businesses destroyed, from deliberate mass infection to inevitable food shortages, from the summary removal of rights, regulations and protections to the degradation of democracy itself. All enacted against not only the occupied nations, but the non-ruling English. And perpetrated by a small group of ideologues, malignant narcissists and sociopaths at the centre in order to extract wealth and to wield power, it would appear, simply for the sadistic enjoyment.

In a tweet posted on July 19th, Limmy made this irony-laced observation: “This Freedom Day experiment is the sort of thing the British Empire would have done to people in another country, partly as an experiment and partly out of malice. So for Boris to do it to his own, to England, it’s actually quite a progressive move.” Sums it all up nicely.

The kleptofascist project’s in-house newspaper The Telegraph reported on July 26th that the Bank of England advocates raising the pension age, something the Tories have floated several times since Brexit, after already increasing retirement age multiple times since 2010. It really does seem as though our ruling class wants us not only to work till we’re dead, but after we’re dead too—just like Plague’s poor exploited zombies.